“Tintic talked to the Indians in a low grunt, thinking I could not catch what he said, [but] I was in too tight a place to observe all that was passing around me.”

The Indians were testing Clark’s courage.

Tintic said, “Wait until he starts home, then we will kill him.” Tintic wanted Clark to hear him say this to the Indians to see if Clark was afraid.

Clark recorded that, “I could see I would have to wait until dark to have a chance for escape.” Clark knew the posse was at the fort and the Chief’s tent was close enough to see him enter and exit back to the fort. It was only half a mile according to a witness, Joseph S. McFate.

It still was not dark. Clark said to Chief Tintic, “telling him that Brigham Young wanted him to come to the fort and talk with Johnson. He [Tintic] only laughed and called President Young bad names and said that he would not go. He was so sullen he wouldn’t talk much. I had to keep talking as I dared not make a move to go.”

From the top of the rock fort wall in Fairfield, Bishop Packer reported seeing the Indians “stripped” paint their bodies in war paints, “and prepared to fight.” This was happening out of Clark’s view, as he was inside the tent. The posse was concerned for Clark’s safety. They recruited more men, including George Carson who lived at the rock fort in Fairfield. As the sun set, the large posse rode to the Indian encampment.

Still inside the tent, Clark heard one of the squaws outside let out a warning. According to Clark, she hollered that the Mormons were coming. Clark reported that when the posse members rode up, ‘Thomas Johnson called out, ‘Are you all right, John?’”

John indicated that he was alright. Next, “Johnson grabbed Tintic by the hair [and] drawing his six-shooter said, ‘You are my prisoner.’ Tintic grabbed [the six-shooter] by the muzzle, it went off shooting him through the hand.” Tintic had this one wound in his hand.

Outside, the posse only knew they heard a shot. So, they opened fire on the Indians.

Tintic pulled loose from Johnson’s grip and ran out the back of the tent.

Bishop Packer said, “Tintic’s brother, Battest, aimed his rifle at George Parish and fired, but the gun barrel being knocked aside, the bullet missed its mark. One of Parish’s friends then drew his revolver and shot Battest through the head, killing him instantly.”

Clark reported, “As I attempted to rise all the rest [of the Indians] either jumped over me or sprang off my back as they went out.” He was flat on the ground with the Indians stepping over him to get out of the tent while bullets were flying all around. Then Clark wrote, “It was the only thing that saved my life.”

A squaw grabbed a spear from the Indians who had been on guard outside the tent, and tried to kill George Carson. George saw her and tried to move out of the path of the point to no avail. The spear still pierced his body, in his leg. In Elvin Carson’s version George Carson was wounded just by an Indian Squaw. According to Richard S. Van Wagoner, George Carson was also shot. Nevertheless, the posse saw George, picked him up, and laid him over his horse. They led his horse with the injured owner into the fort. Meanwhile, Clark got up, collected as many weapons he could hold, and looked for a horse. He jumped on one of the Indians’ horses tied near the tent. Just then, some of the Indians saw Clark, “they began running and shooting, being careful [though] not to hit their horses [horse]” that Clark lay over the side of while riding for his life. Clark raced for the fort.

Several of the Native Americans were dead including Battest and three other Indians. The Tintic Indians with their families ran south of their camp and hid in the juniper trees. Mads Christensen wrote what happened that night. “We could hear moaning and mournings by refugees who, during the night, were moving their camp and effects west into Rush Valley for safety, having some wounded with them and having left one Indian and a squaw on the battleground.”

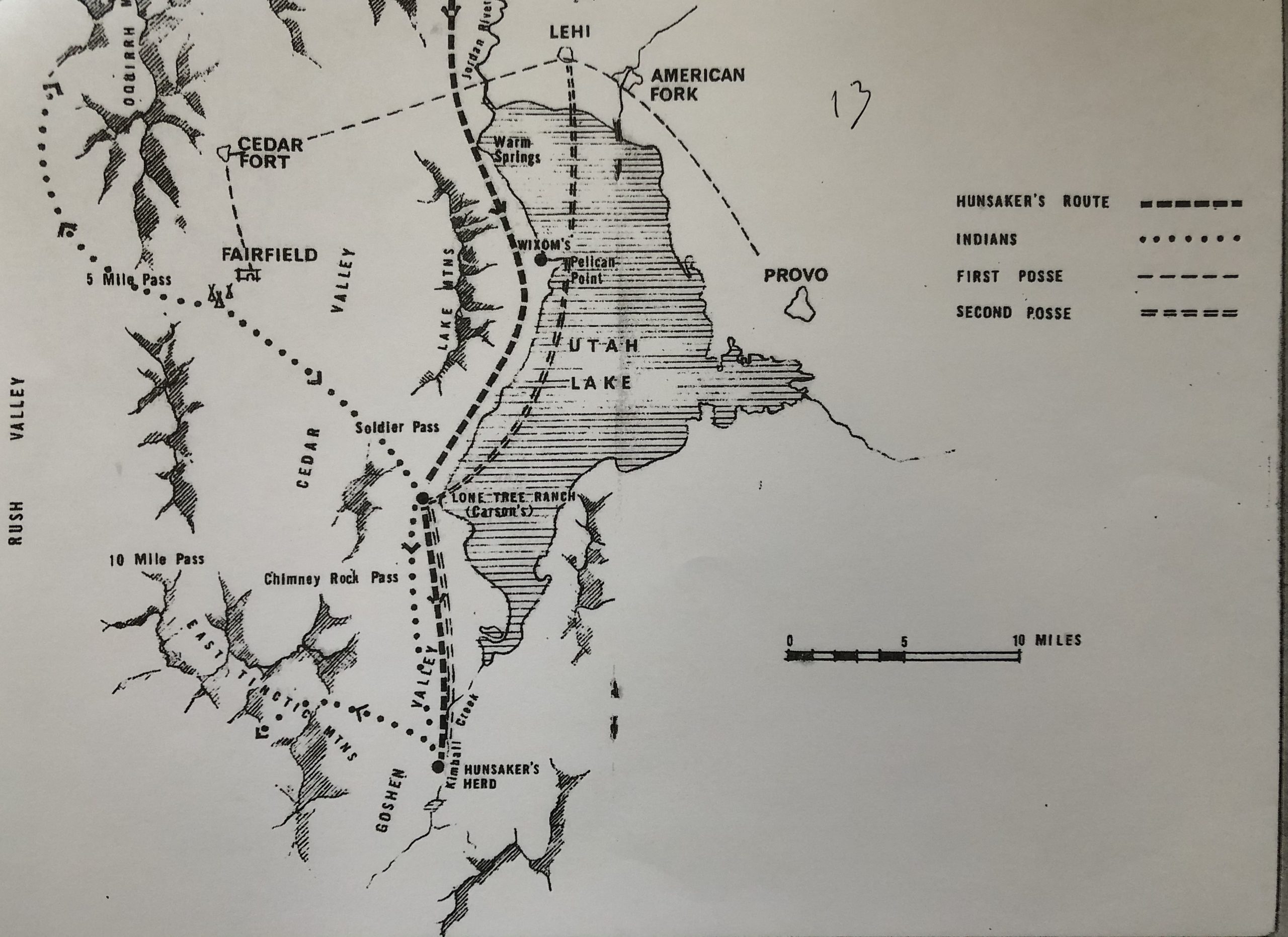

The different groups left the area. In the fort, the wounded George kept bleeding. He died about one o’clock in the morning, on February 23, 1856. Most likely he bled to death. This was the first battle of the Tintic War. During the dark early morning, Tintic’s band of Indians moved east, not west. They quietly went across the southern part of Cedar Valley. The band went straight through the opening to the Utah Valley and the area of Lone Tree Ranch. At the end of the previous year, Elizabeth’s husband Pattison had been farming there and Washington Carson and Henry Moran were herding.

On that same Friday that the posse was preparing to leave Lehi for the rock fort at Fairfield, the posse filled the Lehi men in on the writ for arrests of Chief Tintic and other Indians. One other figure in the story, Abraham Hunsaker left his one home in the Salt Lake Valley. He read the newspaper reports of Indians stealing and the growing hostilities. Hunsaker had a plural wife and her children on the ranch south of the Lone Tree Ranch. He wanted to pick them up and bring them to his first house. Hunsaker wrote that the day began bitterly cold, with snow on the ground. He and his son rode in a carriage as fast as possible to Lehi, and then onto the Hunsaker Ranch and home. First, they arrived at the Lone Tree Ranch where Washington and Henry lived. They had to wait while their horses refreshed; so, they spent the night. That was the same night the Tintic Indians pretended to travel west into Rush Valley.

Chief Tintic may have been innocent of the crime the writ of arrest accused him of, but now his band had killed a “white man.” The chief’s strategy, to make a noisy retreat into the Rush Valley, only to reverse course silently in the early hours of the morning, was to escape a revengeful posse. The Tintic Indians would have to hide in the mountains from posses, but first, they needed a herd of steers. Early on the morning of Saturday, February 23rd, only a small band of squaws and children moved into the Rush Valley, while two groups of braves moved stealthily to the pass into the Utah Valley. Chief Tinitic’s plan was that later the three bands would rendezvous in the mountains to the south.

The next battle would take place at Lone Tree Ranch. Hunsaker and his son awoke before dawn, leaving Washington and Henry. The father and son hoped to get to their family as soon as possible. Hunsaker, the last to see Washington and Henry alive, wrote in his diary about the Tintic Indians attack on the two men at Lone Tree Ranch. The Indians attacked some time after Hunsaker left, killing Washington and Henry. They ransacked the “house” dugout and began herding the Carson herd south.

The third band, two braves, hurried to the Hunsaker ranch and house. According to Hunsaker, it was at ten o’clock in the morning as they were taking the tack off their horses. Two Indians rode towards them furiously. One more Indian who had been friendly with Hunsaker joined them. The three renegades had a discussion about two hundred yards away. Then they headed west. Hunsaker had his wife and all the children, except one boy looking out, safely inside the house. However, Hunsaker knew they could not stay. With only one fresh horse at the ranch, Hunsaker sent his son Lewis to get a mare he had seen two miles north of the house. Lewis jumped on the fresh ranch horse and sped off. The other sons saw the Indians turn and ride after Lewis.

Hunsaker loaded his family into the carriage with the tired horse harnessed to it. He tied as many livestock to it as possible. They herded the sheep and set off to the north. He hoped to overtake Lewis on his way north to the Carson’s ranch. When they were about a mile from Carson’s, Hunsaker sent his son Allen ahead to warn Washington and Henry and get an “express” to Provo for help. Utah Lake was frozen solid and Provo was not far that way. As the carriage neared the dugout, Allen returned to report he found it plundered and nobody there. So, they left the livestock and sheep and hurried to the next ranch, the Wixoms at Pelican Point. The Hunsakers continued north, Mr. Hunsaker with his gun at the ready and Allen with an Ax in hand. Lenuel, who was an adopted son, made up the rear guard “as he was an Indian and could see better than any of us,” Abraham Hunsaker wrote.

About three hundred yards north of the dugout, Hunsaker came across a body. The face was towards the ground. Fearing it was his son Lewis, he looked closely into the face. It was Washington Carson. It was still Saturday, February 23rd. Both George in Fairfield and Washinton Carson at Lone Tree Ranch had died on the same day at the hand of Tintic’s band. Hunsaker thought that he better hurry on to Lehi and in the morning come back for the body with a group from Lehi. On Sunday, the Hunsakers arrived at Pelican Point. Hunsaker left his family with the Wicoms early the next morning and continued north.

More settlers would be gathered in the effort to put down the Indian uprising, later called the Tintic War. Part way, Hunsaker met a company from the Salt Lake Valley under Colonel Brown, who were coming to Carson’s Lone Tree Ranch to get Colonel Brown’s cattle that were grazing there. After Hunsaker explained what the Indians had done, they sent an express messenger to Lehi to rally more men. In Lehi, David Evans raised twenty-five men. This second posse was under the command of Sidney Smith Willis, a commander of the Lehi militia. Willis’ posse crossed from Lehi to Pelican Point on the frozen lake. The posse’s mission was to subdue the Indians and recover the cattle. The militia/posse arrived at the Carson’s Lone Tree Ranch on Monday, February 25th.

At Carson’s, they searched for two bodies. Hunsaker wrote in his diary, “We found Henry Moran, lying flat on his belly with his arms stretched out, dead, being shot with bullets through his body.” It was speculated by Hunsaker that Washington and Henry probably had just left the dugout when one of the three bands of Tintic Indians surprised them right after Hunsaker had left with his son. Now, concerned that the two bands of Indians had rounded up the Carson/Brown herd and the Hunsaker herd. So, the posse with Brown and Hunsaker hurried south to Hunsakers to look for Lewis and the missing herds.

The cowboys rounded up the cattle. The men only found 255 head of cattle which they took to their camp in Goshen Valley. Meanwhile, the rest of the posse (Lehi Militia) rested near juniper trees. Indians in the trees killed Joseph Cousins. The Indians kept up a fight, attacking the camp. During the confusion, the Indians drove off nearly all of the cattle the posse had collected plus seventeen of the horses. George Winn died of his wounds inflicted by the Indians. The second posse (Lehi Militia) picked up some stray cattle and returned them to Hunsaker and the Carsons. Sadly, Hunsaker never found his son Lewis. Hunsaker hoped the friendly Ute Indian from his ranch area had convinced Chief Tintic to keep him instead of killing Lewis.

Back in Fairfield, a messenger informed the Carsons of the deaths of Washington and George. The remains were frozen at the Lone Tree Ranch. So, they would have to wait until the spring thaw. Elizabeth Carson Griffith worried for her husband who had been at the ranch too. Pattison Griffith later returned to Elizabeth’s relief. He had taken the crop from city to city looking for a mill to grind it into flour. Fortunately, Pattison’s life had been spared.

Both of the posses failed to capture Chief Tintic. The bands met up again in the mountains to the south. The braves who had rusted hundreds of cattle and seventeen horses brought them to their mountain camp. They feasted on beef all winter. Chief Tintic lived on until 1859. Ironically, the mountains Chief Tintic and his followers hid out in until his death held a wealth of silver in their veins. Those mountains, the mining district and the old town of Tintic Junction (no longer there) are named after Chief Tintic, who led the Tintic band of Ute Indians.