My second great grandfather, English Mormon immigrant pioneer, William Clark (1825-1910), arrived in Lehi in November, 1853, accompanied by my second great grandmother, Jane Stevenson (1820-1895), their infant daughter, and Jane’s three children from her previous marriage. They acquired an adobe home on the northeastern-most of the sixteen city blocks that were enclosed the following year by a twelve-foot-high mud wall. The Clark’s home faced First West Street. I don’t know when the home was built, but I’m confident it was their home, dwelling 3426, in the 1860 Census. It’s depicted at position 23 on the 1890, 1898, and 1907 Sanborn Fire Insurance maps of the Lehi block bounded on the South by Main Street, on the West by First West Street, on the North by First North Street, and on the East by Center Street (Block 40). William and Jane lived in their pioneer adobe home until their deaths, Jane in 1895, William in 1910. The home was removed in 1930, twenty years after William’s death, to make way for the Lehi High School/Junior High School athletic field. The site is now covered by asphalt on the parking lot south of the Lehi Legacy Center.

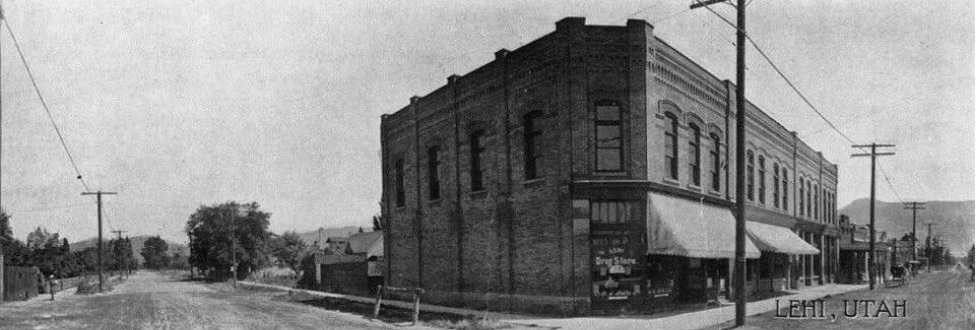

The 1890 and 1898 Sanborn maps depict seven additional adobe homes on Block 40 in Lehi. One of these, a substantial dwelling at position 18/19, faced First West Street, south of the pioneer adobe home of William Clark. It occupied the site on which the Merrihew/Dalley building now stands on the Northeast corner of the intersection of First West and Main Streets. That building was constructed in 1900. It’s labelled “Drugs” on the 1907 Sanborn map. The Position 18/19 home may have stood partially on the footprint of the adjacent building, labelled “DG” (dry goods) on the 1907 map. Utah

County Recorder’s Office records show that Paulinus Harvey Allred (1829-1900) received the Mayor’s deed for the property on which the Position 18/19 home stood in 1871. The property was sold to H. B. Merrihew in 1900. S. W. Ross built a large building next to it on the site which in 1989 was the Laney building.

Twenty-two-year-old Paulinus Allred, designated as a “cordmaker,” was with his wife, 25-year-old Melissa [Melissa Isabell Norton (1824-1892)] and three children in Great Salt Lake, Utah Territory, in the 1850 Census (taken in 1851). A biography titled Paulinus Harvey Allred 1829-1900 says the Allreds moved to Lehi in 1854 where they “built an adobe home near the center of town” and raised a family of eight children. The Position 18/19 adobe dwelling fits that description. The Allreds and six children were in the home in Lehi in dwelling 3427 in the 1860 Census. William and Jane Stevenson Clark and their seven children were nearby in the Position 23 home, which was dwelling 3426, in the 1860 Census. The Allreds were in dwelling 7 in the 1870 Census.

William Clark spoke at Melissa Isabell’s August, 1892, funeral. He “spoke in eulogistic terms of the deceased and offered consoling remarks to the relatives and friends” at the services that were held “at the family residence.” Melissa Isabell’s obituary asserts the day previous to her death in 1892 she walked 125 yards to see the procession on “July 25th”. It would seem that if she and Paulinus had stayed in the Position 18/19 home the procession would have passed her home on Main Street and she would not have had to walk at all. In fact, the Paulinus Harvey Allred family had moved. The Clark’s were in dwelling 20 in the 1880 Census. Their neighbors that year were Isaac Harvey Allred (1850-1923), his wife Ursula Mulliner (1854-1914), and three children in dwelling 19 in the 1880 Census. Isaac was a son of Paulinus and Melissa Isabel Allred. Isaac and Ursula appear to have moved into the Position 18/19 adobe in which Isaac had lived previously with his parents.

Paulinus Allred’s biographical sketch says that he grew the first stack of alfalfa hay in Lehi in 1867. That stack of hay may have been between the Allred’s adobe home and the Clark’s adobe home there on First West Street. Remains of the hay might be found today under the asphalt of the South end of the Lehi Legacy Center parking lot.

William Clark probably grew alfalfa in his fields south of Lehi. His grandson, my grandfather, Asa Jones Clark (1882-1966), raised alfalfa down there, with the help of his sons and son in law. In my youth I was obliged to work with the stuff, loading bales onto trucks and offloading them onto haystacks in the fields or in barns. For me it was the cause of incessant sneezing and gasping for breath. I hated it. I didn’t learn the fine points of alfalfa cultivation. I escaped the tyrannous rigors of Lehi agricultural field work by going off to college. There I was introduced to field work related to scientific investigations. I actually got college credit when I took a two-month-long field trip to Mexico with a Brigham Young University professor and another student. We loaded our gear into a pickup truck with a camper and headed south from Provo. Our first night in Mexico we pulled way off the highway somewhere in Chihuahua. There we had the first of many meals of canned spam and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches served from the tailgate of the truck. While we washed that down with water, we listened to the news on a transistor radio. The big story that night was the Israeli invasions of Egypt and Syria that commenced the Six-Day War.

After puttering around among the mesquite and prickly pear cactus, we stuffed ourselves into the camper and closed the tailgate. After a peaceful interlude, and before sleep overtook me, we began to hear Spanish speaking voices and gunfire. Those were not pleasant sounds. I felt vulnerable out there in the desert. The sounds seemed to come closer, then faded as the shooters moved on. The chatting shooters evidently either overlooked us or decided not to bother us. We continued south. We collected beetles called bark beetles (Scolytidae) from trees in deserts and jungles, in mountains and in valleys in central and southern parts of the country. We camped and ate our spam and peanut butter, supplemented from time to time by meat purchased in outdoor markets of towns and villages along the way.

I was hooked on that sort of field work. Collecting insects around Provo was almost as interesting as looking for them in the wilds south of the border. I gravitated from bark beetles to weevils (Curculionidae) as the chief objects of my interests. I learned that alfalfa was a very common plant in Utah County. I discovered that it grew along roadsides and waste places just about everywhere in the valley. Wherever the alfalfa was found, the alfalfa weevil was sure to be there. Adult and larval alfalfa weevils could be observed feeding on the leaves of the clover-like plants. I learned that the alfalfa weevils, like the alfalfa plants, and like the Mormon people who lived in Utah and grew the crop for their European livestock, were all European introductions. The weevils came after the Mormon’s and after the alfalfa. Interestingly, the weevils made their first North American appearance in Utah.

I don’t know if alfalfa weevils were a problem for my grandfather or not. I don’t recall ever hearing mention of them. Not long after I did that field work in Mexico my wife and I made a trip to southern Alberta. I told a good farmer friend there about the trip to Mexico and the beetles. He was indignant that anyone should spend time and money on such pursuits. I asked him if he had problems with alfalfa weevils on his alfalfa crops there. He assured me he did not. When I got to Texas and to Alabama I met a lot of farmers who had more appreciation for entomologists. I doubt there ever was a farmer down there who didn’t have problems with weevils of some sort. I was able to actually get paid to deal with those weevils in one way or another. I don’t think I would be able to explain all of that to William Clark or to Paulinus Harvey Allred or to any of their neighbors on the Memorial Building block during pioneer times in Lehi. They would likely be quite bemused and perhaps indignant about a lot of the things people spend their time and money on today here in Lehi.

Note : This story is drawn from information in the following documents which contain the supporting references and documentation.

The Old Fort Wall, a Herd of Cows, and a Near and Dear Neighbor in Lehi, Utah

Melissa Lott Smith Bernhisel Willes and three Joseph Smiths

My “Aunt Melissa:” Melissa Lott Smith Bernhisel Willes

William Clark (1825-1910): His Pioneer Adobe Home in Lehi, Utah, and the Homes of his Neighbors and Descendants

Pioneer Adobe Homes on the Memorial Building and Legacy Center Blocks in Lehi, Utah