The Knudsens of Lehi Utah had four Japanese Americans relocated to their house. The following excerpt is quoted from the unpublished history of the Knudsen family by Racheal Lillian Knudsen (1899-1982).

“Not long before World War II commenced, Fred (her husband Frederick Christian Knudsen) obtained employment in the Lehi Roller Mills which was supplying flour to the government for the war effort, and we moved into the old family home with my mother who welcomed us with open arms. This was a delightful time for me to be able to spend time with my beloved mother and feel the warmth of my old home once again.

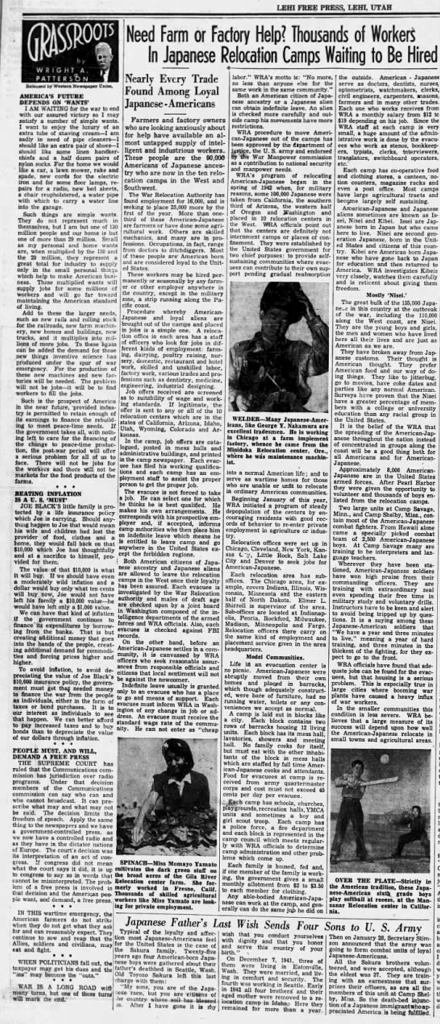

During World War II, while Fred and I were living with my mother in the old family home, my mother utilized a government program to sponsor four Japanese families who were living in the government internment camps under horrible conditions. My mother, always generous to a fault, was anxious to provide a temporary home to these strange people and to provide some extra income. The house was renovated into apartments to accommodate them. The Japanese men, and some of the women, worked out in the community, mostly at the sugar beet fields, and paid my mother a stipend from their wages for housing. Some of them, who had no employment, worked on our family farm and at the house as servants. In time my mother came to love and admire these good people who suffered hardships only due to their race during a war with their former country. …I can’t recall all of their names. Not only were they difficult to pronounce and remember, but some of these families stayed only a short time and then moved on back to the camps or other places and who eventually regained their citizenship status when the war ended…

The one (Japanese) I remember best was a kind man named Tsuneo, whom we referred to as “Harry,” and his little wife Vary. Harry worked at the Lehi Sugar Plant but when he came home, and in his spare time, he worked in my mother’s yard and gardens, and he soon had them shaped up to be the showcase of Lehi. It was my understanding that he had worked in professional nurseries in his California home before he had been transferred to the internment camps. His little wife Vary took care of mother’s home and she wouldn’t allow my mother to lift a hand before she would rush to do the chore. She once made tea for my mother who told her she did not drink tea as it was against her religion, and I think it hurt Vary’s feelings a little, as though she had done something wrong, but my mother told her it was not her fault that she didn’t know. …

Harry, the Japanese man who lived in our family home, was such a nice man. He politely bowed every time he entered the room and every time he left it. He was well educated and spoke English very well without a noticeable accent. He talked about growing up in California, somewhere in the San Francisco area, and said that his ability to speak English was due to a language school he had attended. I thought it so endearing that every day he would cut a rose from mother’s garden and bring it to his little wife Vary, bowing as he did so, and she curtsied as she accepted it. I don’t know what happened to them when the war was over and they were released from the bonds of prejudice. I presume that they returned to their home in California but as far as I know my mother never heard from them again.”